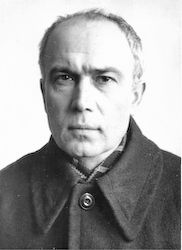

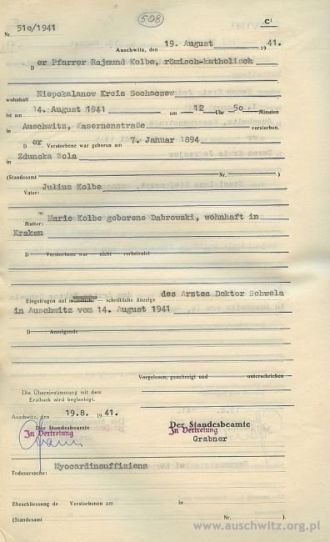

Today is the 76th Anniversary of the death of St. Maximilian. We publish the interview with Michał Micherdziński, one of the last witnesses of the sacrifice of St. Maximilian Kolbe instead of a fellow prisoner, made the night of 29-30 July 1941 in the concentration camp Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Interview by Fr. Witold Pobiedziński

— You were prisoner in the Auschwitz concentration camp for five years. You personally met St. Maximilian Maria Kolbe there. How important for you and the other prisoners was the presence of this monk amongst you?

— You were prisoner in the Auschwitz concentration camp for five years. You personally met St. Maximilian Maria Kolbe there. How important for you and the other prisoners was the presence of this monk amongst you?

All prisoners coming to Auschwitz were greeted with the same words: “You did not come to a sanatorium but to a German concentration camp from which there is no other way than through the chimney. Jews can live for two weeks, priests live a month, and the rest live three months. Those wo do not like it may just go to the wire.” This meant that they could be killed, because there flowed nonstop high-voltage current in the wires surrounding the camp. These words announced at the beginning of their detention deprived the prisoners of hope. I was granted incredible grace in Auschwitz, because I stayed in one block with Fr. Maximilian, and I was standing with him in one row at the time of the selection for death. I was an eyewitness of his heroic sacrifice, which brought hope back to me and other prisoners.

— What were the circumstances of this event, which is still of so great and keen interest and inspires people to ask the question: Why did he do it, what values did he stand for?

— What were the circumstances of this event, which is still of so great and keen interest and inspires people to ask the question: Why did he do it, what values did he stand for?

63 years ago, on Tuesday, July 29, 1941, at about 1.00 o’clock, just after the midday roll call, the alarm sirens howled. More than 100 decibels went through the camp. The prisoners, by the sweat of their brow, were fulfilling their duties. The howl of sirens meant the alarm, and the alarm meant that some prisoner was missing. The SS immediately stopped the work and began escorting prisoners to the camp for roll-call to check the number of prisoners. For us who worked on the construction of a nearby rubber factory, it meant a seven-kilometre march to the camp. We were rushed to report back.

Roll-call showed a tragic thing: There was one prisoner missing from our Block 14a. When I say “from our block” I mean that of Fr. Maximilian, Franciszek Gajowniczek, others and myself. It was a frightening message. All other prisoners were relieved and were allowed to go back to their blocks, and the penalty was announced to us — standing at attention without caps, day and night, hungry. The night was very cold. When the SS had a changing of the guard, we crowded together like bees — those standing outside warmed those in the middle, and then there was a change.

Many older people could not withstand the agony of standing in the night and in the cold. We wished for at least a little sun to warm us. We also expected the worst. In the morning, the German officer shouted at us: “Because a prisoner escaped from your block and you did not prevent it or stop it, ten of you will die of starvation in order that the others will remember that even the smallest attempts to escape will not be tolerated.” Selection began.

— What happens with a man when he knows that this may be the last moment of his life? What feelings accompanied the prisoners who could hear the sentence condemning them to death?

— What happens with a man when he knows that this may be the last moment of his life? What feelings accompanied the prisoners who could hear the sentence condemning them to death?

I’d rather spare myself remembering the details of this terrible situation. I will tell generally what the selection looked like: The whole group went to the beginning of the first line. At the front, two steps ahead of us, a German captain was standing. He looked you in the eye like a vulture. He would measure each of us and then raise his right hand and say, “Du!” that is “You.” This “Du!” meant that you will die of starvation, and he would go on. The SS-men dragged the unfortunate prisoner out of his place in the row, wrote down the number, and set him aside under guard.

“Du!” sounded like a hammer hitting an empty chest. Everyone was afraid that anytime the finger might point at him. The line under scrutiny moved a few steps forward, so that between the lines being scrutinized and the next line something like corridors formed, with a free space of a width three to four meters. The SS-man walked along this corridor and again said, “Du! Du.” Our hearts thudded. With noise in heads, blood throbbing in temples, it seemed to us that the blood would spring out of our noses, ears, and eyes. It was something tragic.

— How was St. Maximilian behaving during this selection?

— How was St. Maximilian behaving during this selection?

Fr. Maximilian and I were standing in the seventh row. He stood on my left; perhaps two or three friends separated me from him. As the rows behind us dwindled, more and more fear started enveloping me. I must say, no matter how much a man is determined and frightened, no philosophy is then needed for him. Happy is the one who has a faith, who is able to fall back on somebody, to ask somebody for the mercy. I prayed to the Mother of God. I must honestly confess it; I had never before nor afterwards prayed so zealously.

Although there was still heard “Du!” ,the prayer inwardly changed me, enough for me to be calmer. People having a faith were not so terrified. They were ready to accept destiny with peace, almost like heroes. It is great consolation. The SS-man passed me by, sweeping with his eyes, and then passed Fr. Maximilian by. He “liked” Franciszek Gajowniczek standing at the end of the row, who was a 41-year sergeant of the Polish Army. When the German said “Du!” and pointed at him, the poor man exclaimed, “Jesus, Mary! My wife, my children!” Of course, the SS-men did not take notice of the words of prisoners, and just wrote down his number. Gajowniczek later swore that if he had died in the hunger bunker, he wouldn’t have known that such a lament, such an imploring request came out of his mouth.

— After the selection was finished, did the remaining prisoners feel relief that the great terror was over?

The selection ended. The ten prisoners were already chosen. It was a closing roll-call for them. We thought that this nightmare of standing would end: our heads ached, we wanted to eat, our legs were swelling. Suddenly some commotion started in my row. We stood at intervals the length of our clogs apart, when all of a sudden somebody began going forward between prisoners. It was Fr. Maximilian.

He was going by in short steps, since one could not go by long strides in clogs, because it was necessary to curl one’s toes in order keep the clogs from falling off. He was going straight towards the group of SS men, standing by the first row of prisoners. Everyone shivered, since this was breaking one of the most insisted upon rules, the breaking of which was brutally punished. The exit from the row meant death. New prisoners arriving to the camp, not knowing about this ban against leaving the row were beaten until they were incapacitated from work. It equalled going to the starvation bunker.

We were certain that they would kill Fr. Maximilian even before he managed to get through. But something extraordinary happened that was unheard of in the history of seven hundred concentration camps of The Third Reich. It has never happened that a prisoner of a camp could leave the row without being punished. It was something so unimaginable for SS men that they stood dumbfounded. They looked at each other as they didn’t know what was happening.

— What happened next?

— What happened next?

Fr. Maximilian walked in his clogs and striped prison uniform with his bowl at his side. He didn’t walk like a beggar, nor like a hero. He walked like a man conscious of a great mission. He stood calmly before the officers.

The camp commandant finally came to his senses. Furious, he asked his deputy, “Was will dieses polnische Schwein?” (What does this Polish swine want?). They started looking for the translator, but it turned out that the translator was unnecessary.

Fr. Maximilian answered calmly: “Ich will sterben für ihn,” pointing with his hand at Gajowniczek standing beside: “I want to die instead of him.”

The Germans stood speechless with their mouths open with amazement. For them, representing the secular ungodliness, it was something incomprehensible that somebody may wish to die for other man. They looked at Fr. Maximilian with the questions in their eyes: Has he gone crazy? Maybe we didn’t understand what he said?

Finally the second question was put forward: “Wer bist du?” (Who are you?).

Fr. Maximilian answered, “Ich bin ein polnischer katolischer Priester.” (I am a Polish Catholic priest). Here the prisoner confessed that he was Polish and comes from the nation which these Germans hated. Further, he was admitting that he is a clergyman.

For SS men, the priest was a twinge of conscience.

It is interesting that, in this dialogue, Fr. Maximilian did not once use the word “please”. With his statement, he broke the German’s usurped authority to decide on life and death, and he forced them to change the sentence. He behaved like an experienced diplomat. Only instead of a tailcoat, a sash, and medals, he presented himself in striped prison garb, a bowl, and clogs. The deathly silence prevailed, and every second seemed to last centuries.

Finally something happened, which neither the Germans nor the prisoners can understand to this day. The SS captain turned to Fr. Maximilian and addressed him formally with “Sie” (formal “you”) and then asked, “Warum wollen Sie für ihn sterben?” (Why do you want to die instead of him?).

All canons, which the SS man confessed earlier, fell apart. A moment ago he had called him the “Polish swine,” and now was turning to him with “Sie.” The SS men and non-commissioned officers standing beside him weren’t sure whether they heard right. Only once in the history of concentration camps had the high-ranking officer who murdered thousands of people addressed a prisoner this way.

Fr. Maximilian answered, “Er hat eine Frau und Kinder” (He has a wife and children).

It is the entire catechism in a nutshell. He taught everyone what fatherhood and family means. He was a man with two doctorates obtained in Rome with “summa cum laude” (highest possible with honour), editor, missionary, academic teacher of two universities in Cracow and Nagasaki. He thought that his life was less worth than the life of the father of a family! It was a wonderful lesson in catechism!

— How did the officer react to words of Fr. Maximilian?

Everyone was waiting to see what would happen next. The SS-man was convinced that he was the master of life and death. He could order him to be beaten badly for breaking the most strictly followed rule of stepping out of the line. And more importantly, does a prisoner dare preach morality?! He could sentence both to death by starvation. After a few seconds, the SS-man said, “Gut” (very well). He agreed with Fr. Maximilian, and admitted that he was right. It meant that the good won over evil, the maximum evil.

There is no greater evil than to sentence a man to death by starvation through hatred. But neither is there a greater good than to give one’s own life for another man. The maximum good won. I want to stress the replies of Fr. Maximilian: He was asked questions thrice and thrice he answered concisely and briefly, using four words. Number four in the Bible symbolically means the entire man.

— How important was it for you and the remaining prisoners to be eyewitnesses?

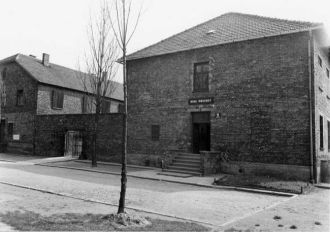

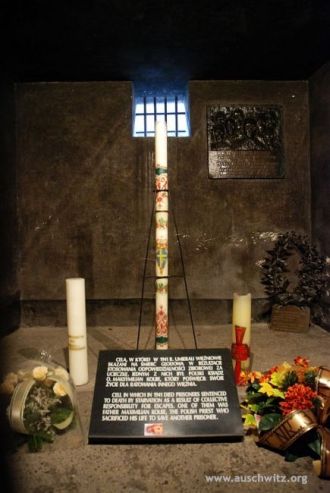

The Germans let Gajowniczek back to the line, and Fr. Maximilian took his place. The convicts had to take their clogs off, because they were already unnecessary. The door of the hunger bunker was opened only in order to take bodies out. Fr. Maximilian walked in as one of the last pair, and he even helped the other prisoner to walk. In principle, it was their own funeral before death. In front of the block, they were told to take the striped uniforms off and were thrown into a cell with an area of eight square metres. Sunlight seeped through the three bars of the window onto the cold, rough, wet floor, and black walls.

Another miracle happened there. Fr. Maximilian, although he had been breathing only with one lung, survived all. He was alive in the chamber of death 386 hours. Every doctor will recognize that this is incredible. After this horrendous period of dying, the executioner in white medical overalls gave him a lethal injection. Yet again, he didn’t die…. They had to finish him off with a second injection. He died on eve of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, his Hetmanka (Commander in chief of the armies). He wanted to work and die for the Immaculate Mary throughout his life. It was the greatest happiness for him.

— Referring to the first question, be so kind and add, please, what did this extra-ordinary attitude of Fr. Maximilian mean for you, being rescued from death by starvation?

The sacrifice of Fr. Maximilian inspired a lot of work. He strengthened the activity of the camp group of the resistance, the underground prisoner organization, and it divided the time into “before” and “after” the sacrifice of Fr. Maximilian. Many prisoners survived the camp, thanks to the existence and operation of this organization. A few of us were rescued, two in every hundred. I received grace, because I am one of these two. Franciszek Gajowniczek was not only rescued but also lived another 54 years.

Our saintly fellow-prisoner rescued, above all, the humanity in us. He was a spiritual shepherd in the hunger chamber, supported, led prayers, absolved sin, and led the dying out to the other world with the Sign of the Cross. He strengthened the faith and hope in us who survived the selection. Amidst this destruction, terror, and the evil, he restored hope.

Save

Save